by Seth Kalkala

What factors propelled Joe Biden to victory in the November 2020 election? Did voters abandon Donald Trump in droves? Are liberals, socialists, and statists gaining ground in the United States of America?

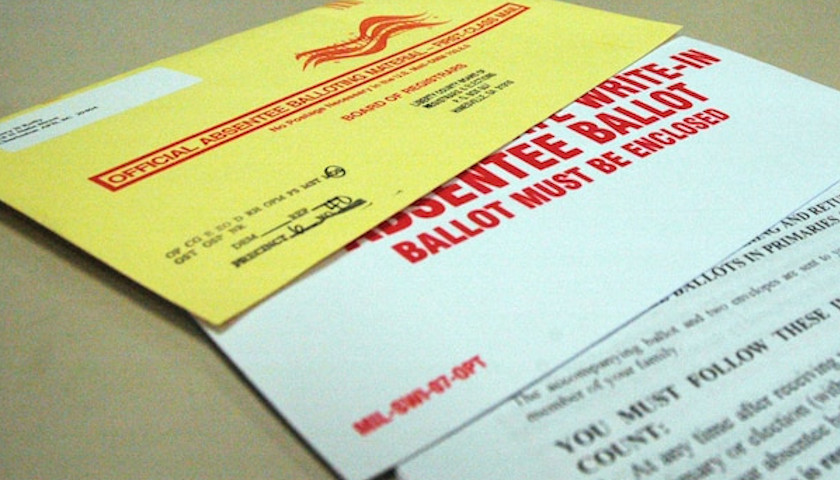

I don’t think so, but I don’t have a definitive answer for you. Neither, so far as I know, does anyone else. After diligently examining the numbers and reviewing news reports from each state east of the Mississippi River, all I can say with confidence is that mail-in voting had something to do with why Biden prevailed. If some pundit or politician claims it was due to this or that cohort of “swing voter,” or to some malfeasance on the part of Donald Trump, or because voters wanted a return to “decency” under “nice guy” Joe, well … be skeptical.

Biden trounced Clinton, and Trump 2020 pummeled Trump 2016

So you thought the election was only about Biden defeating Trump? Think again — it also was the case that Joe Biden surpassed Hillary Clinton’s 2016 vote count in every state east of the Mississippi by at least a 10 percent differential, and in most cases by 20 to 35 percent. Donald Trump 2020 also roundly defeated Donald Trump 2016, but usually by lesser margins compared to Biden versus Clinton. Only in Florida, New York, and Illinois did Trump’s margin over his former self exceed the gap between Biden and Clinton.

Quantifying Joe Biden’s wide margins over Hillary Clinton alongside Trump’s substantial gains over his former self might seem like a nonsensical and futile exercise. But it actually underscores two important points that pundits and politicos typically ignore when “explaining” the 2020 presidential election.

The introduction of mass mail-in voting was a game-changer; it brought with it a slew of confounding factors.

First, framing the election this way invalidates the frequently proffered, simplistic claims that Biden “flipped” this or that locality or state or that he “won over” this or that “disaffected” segment of voters. Both candidates achieved large vote gains, and the fact that Biden’s gains were larger does not imply that he had convinced any sizable cohort to abandon Trump.

Second, the flood of new voters was a correlate of, and undoubtedly tied to, states greatly relaxing their criteria for accepting absentee or mail-in ballots and for voting prior to Election Day. The introduction of mass mail-in voting was a game-changer; it brought with it a slew of confounding factors.

Hence, it becomes difficult to pin down the fundamentals that propelled Biden’s stronger showing. In other words, the significantly altered voting process impedes drawing conclusions based on simple comparisons between 2016 and 2020.

It is possible, for instance, that individuals who naturally lean Democrat were more prevalent within the population benefitting from the new voting flexibilities. According to this scenario, the new voters in 2020 were people who would have sat it out if their only option were to vote in person on Election Day. Additionally, they mostly hold views that align with liberal Democrats. This scenario implies that Clinton would have won the 2016 election if the process then were as flexible as in 2020.

It also is conceivable, of course, that voter sentiment had shifted away from Trump, independent of the new voting processes. In this case, Biden would have won even if there had been no change in voting procedures. It is a daunting challenge to determine whether and to what extent either of these scenarios applies, or to observably distinguish between them.

A jumble of confounding factors

There is yet another possibility, which places even more emphasis on the effects of mass mail-in voting. That is, the mass mail-in process changes not just whether or how people vote, but it can also affect for whom they vote.

One issue is that persons voting by mail prior to Election Day are subject to multiple external influences on their decision-making, from which those voting within the privacy of an election booth on Election Day are comparatively insulated. These influences may be fleeting or superficial and yet still be the determining factor for someone’s voting decision when using a mail-in ballot. Moreover, to the extent that voters sending in their ballots by mail consist of new voters who had sat out the last time due to apathy or indecisiveness, they may be a population more easily swayed by external influences.

For instance, a mail-in voter may impulsively be moved to vote one way or the other while watching a TV opinion show or reading a social media post with a mail-in ballot nearby ready to be filled in. Another might be scolded by a family member who is insisting on a vote for a particular candidate. To seal the deal, the insufferable relative might then offer to deliver the filled-in ballot to a drop-off box (conditional, of course, on the “correct” voting decision).

Mail-in voting also is conducive to vote harvesting, which can take on a variety of forms and intensities, ranging from marginally within the law but ethically questionable to patently illegal. Aside from the previous example of the overly aggressive family member, vote harvesting may take the form of seeking to influence elderly shut-ins, or persons at long-term care facilities, or other individuals who have requested assistance, by whoever is ushering them through the process.

Furthermore, depending on how the mail-in ballot program has been implemented, systemic biases may arise. In a previous article for The American Spectator, I described how automated mail-outs of absentee ballots in Pennsylvania for the general election to individuals who had voted in the state primary likely favored Democrats.

Relatedly, there have been some claims about strategic positioning of drop-off sites for mail-in ballots that advantage one party, by placement in or close to neighborhoods where the party’s registered voters are concentrated.

Finally, it is widely recognized that mass mail-in voting can facilitate outright fraudulent voting or vote counting. Extensive analysis of the association between mail-in voting and fraud, as well as new statistical evidence based on data from the 2020 presidential election in Georgia, are presented in recent research papers by Ph.D. economist John Lott, accessible here and here.

These aspects of mail-in voting, again, are very hard to gather data on and quantify. But the notion that voter sentiment fundamentally shifted toward Biden and the Democrats seems particularly ill-conceived from this perspective.

Geography-based inferences

The above logic also invalidates most geography-based inferences, such as assertions that a county was “flipped” by Biden. Or, for example, observing that a county or set of counties was influential in “flipping” a state does not imply that the demographics within those counties are the relevant factor.

For instance, in two suburban Milwaukee counties (Ozaukee and Waukesha), Biden’s vote gains (his margin over Clinton’s 2016 vote count) were much larger than Trump’s, and more so than in other Wisconsin counties. Thus, these two counties do appear to have been most influential in Biden’s “flipping” Wisconsin.

But each candidate achieved substantial gains in these two counties, and we cannot say that Biden’s gains were larger because some cohort of voters (such as “suburban women”) forsook Trump. Thus, singling out these two counties for special notice does not really provide a whole lot of new information.

The reasons for Biden’s outsized gains in these counties remain unknown — various anecdotes or speculative explanations may have been offered, but to my knowledge there has been no survey-based, statistically rigorous analysis. Moreover, one cannot draw inferences about suburban voters in general based on these two suburban Milwaukee counties.

Some other geography-based claims appearing in news reports are just flat-out incorrect. For instance, it is commonly asserted that Biden’s win in Pennsylvania was largely attributable to voting outcomes in the suburbs of Philadelphia. Sen. Pat Toomey, among others, has done so. With all due respect to Sen. Toomey, this assertion is based on faulty math and logic. Measuring an individual county’s contribution to the “flipping” of a state actually involves some mathematical subtlety, which can lead to erroneous conclusions — and has (providing fodder for a future essay).

There’s one main conclusion

Ideally, mail-in voting should be limited to those with valid reasons for not being capable of voting in person (although in-person voting need not be limited to a single day.) If, however, mass mail-in is to become the norm, then additional safeguards are needed to ensure fair elections and prevent irregularities. Ballot distribution and collection processes must be carefully designed to be free of inherent biases. Rules and procedures must be adopted that adequately mitigate the potential for vote-harvesting activity. And, last but not least, more effective guardrails need to be in place to prevent vote fraud, including that in every state, the voter registration roll must be accurate and up-to-date and signature verification required. Absent such safeguards, mass mail-in voting could well bring about one-party rule in the United States long into the future.

– – –

Seth Kalkala has a B.A. in mathematics and Ph.D. in economics, has many years experience in economic research, and is now semi-retired. Kalkala is a contributor to The American Spectator.